“The temple of costly experience”. That was how Patrick Gwynne’s father, Commander Alban Gwynne, described The Homewood, the house Patrick Gwynne built for his parents when he was just 24.

Patrick Gwynne (1913 – 2003) was born into a wealthy family and showed an enthusiasm for architecture at a young age, joining the office of John Coleridge, a former assistant of Edwin Lutyens. His attention, however, was soon diverted towards the modern movement in the continent. Having sought employment more suitable to his own interests, he ended up in the office of Wells Coates, where he worked alongside Denys Lasdun.

He left in 1937 to undertake his first, and arguably most significant, commission - The Homewood, Surrey. Finished in May 1938, it is the largest and most accomplished translation of Corbusian domestic architecture to be achieved in this country during that pioneer period. But Gwynne's precocious debut wasn’t a polite copy; The Homewood is modernism translated into a British context.

The Homewood, was designed on a generous budget for the time (£10,500). The general form of the house, with its principal rooms elevated at first floor level, was inspired by Corbusier's Villa Savoye. There is one large living room with a dining area screened at one end. The five bedrooms are in a separate wing and the servants’ quarters had room for four servants. The influence of Mies van der Rohe is apparent in the wall of marble in the huge living room - a device seen in the architect's Barcelona Pavilion and Tugendhat House. Reinforced concrete construction and the use of huge areas of glass give the house a typically Modernist transparency and openness.

The timing of the house was unlucky; war broke out just after its completion. Commander Gwynne resumed his naval duties, Patrick joined the RAF and his sister, Babs, went off to the Wrens. Patrick's mother Ruby let the house, but died along with her husband in 1942. After the war, Patrick returned along with his sister, who soon married and left. But Patrick wasn't alone. His long-term companion, pianist Harry Rand, occupied an adjoining bedroom, kitted out identically to Patrick's, with a single bed and washbasin concealed behind sliding panels.

In 1946 he restored the house for himself, re-modelling the kitchen to the servantless times (though he continued to be looked after by housekeeper friends). His parents' bedroom was added to his office space. Murals by Peter Thompson and Stephan Knapp, and furniture to Gwynne's own design, were added over the years. He continually modified the house over time so that it represents design from the 30’s and 50’s to the 70’s.

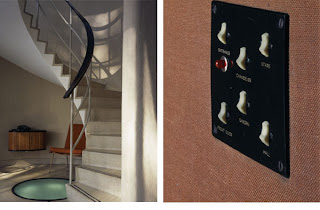

The Homewood, like many of the houses Gwynne went on to build for celebrity clients, including actors Jack Warner and Laurence Harvey, was a party house. During the 40s and 50s, the large sitting room was furnished with light, movable furniture that could make room for dancing on the sprung maple floor. In the 60s, one wall of the room was re-modelled with fibreglass sheeting to improve the acoustics. Hi-fi equipment is integrated into the room's design, as are facilities for making the perfect cocktail, down to a serving table that pivots out from the wall.

Gwynne loved his gadgets. An aluminium, wall-mounted clock has numbers drilled into its face. A magazine table has a little pull-out shelf on which to put a glass. An aerodynamic desk has cine film editing equipment built in. Gwynne designed them all. In the dining room, the flick of a switch could change the colour of the lighting. Rumour has it that if he changed it to green, you'd been branded a bore.

Decor at the Homewood never stood still. Gwynne liked the new, particularly plastics. "He even liked Ikea," says the house's curator, Sophie Chessum. The walls were originally covered with Japanese grass paper, which was replaced by vinyl imitations of grass paper when that first appeared on the market. "By the 60s, he was using hessian in bright, primary colours on the walls. And everything would match: towels, chair cushions, the lot," she says.

The interior spaces include an austere study complete with starship-enterprise-style desk and a vast living and dining area flooded with light from a wall of floor to ceiling windows that look out across the spectacular grounds. 20th century design classics by Bertoia, Breuer, Mathsson, William Plunkett, Saarinen and Eames amongst others are scattered throughout the house. Every inch of space has been carefully considered and designed down to the last detail, there is an oddly shaped drawer or cupboard specially created for every object.

Purists visiting the house now may be dismayed that it is not a shrine to late 30s design. "But that's what's so great about the place," said V&A curator Gareth Williams, who visited just before Gwynne died. "It's a 30s, 50s and 70s house in one. There are layers of living there, and all the many things he made over the years."

The building was his personal masterwork, his home, his office and living portfolio. It's one of the few pre-war modernist houses with continuity of occupation and contents. Nearly everywhere you look around The Homewood, you'll be treated to a wonderful collection of furniture and fittings inspired by the Modernist movement.

The coincidence of its comprehensive publication in the Architectural Review of September 1939 with the outbreak of war perhaps prevented his extraordinary achievement reaching the wide audience it deserved. However, it has now come to be recognised as a masterpiece of the era. In 1994 the National Trust announced that it had accepted Gwynne's offer of the house with most of its contents and its seven-acre garden as a legacy.

He spent his last years overseeing repairs and was responsible for every decision. Before he died, in May 2003, Gwynne insisted it be open to small groups for one day a week for six months of the year. Those who visit will get a glimpse into the world of the man, his taste and vision.

All images by Dennis Gilbert and taken from the National Trust website.

Drawings can be viewed on the RIBA's drawing collection:

Appointments to visit the Homewood must be made through the National Trust on 01372 471144.

Email: thehomewood@nationaltrust.org.uk

http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/main/w-thehomewood

No comments :

Post a Comment